They Went for a Little Walk: The Mummy in Fact, Folklore, Fiction, and Film, Part 1

“[He Dexiu] climbed down into the grave, carefully lifting the woman up to the light to inspect her more closely. Explaining how he had felt when embracing this perfect woman from before the dawn of history he said: ‘That moment as I held her in my arms and looked at her lovely face, I knew she was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. I knew then that if she were alive today, or if I had been alive 3,000 years ago, I would most certainly have asked her—I would most certainly have made her my wife.’”

—Howard Reid, In Search of the Immortals: Mummies, Death and the Afterlife

Human beings, along with elephants and perhaps a few other creatures, recognize the kinship between the dead ones of our species and ourselves. Therein lies much of the motivation and impact of organized religion; there lies, among other things, the soul of the horror genre.

Human beings, for many thousands of years, have buried their dead. Back to prehistoric times they often included in the burial objects that they assumed the dead would need in some form of afterlife. Under certain naural conditions—sometimes by wetness, sometimes by dryness, sometimes by heat, sometimes by cold—a human body can be preserved for an extraordinary time. Some cultures discovered this preservation, probably seeing it as a sign of divine favor. Some of these ancient peoples sought ways to enhance the preservation of their venerated dead through technological remains.

Scientists call on well-preserved human or animal a mummy, whether that preservation is by technological or natural means. A famous example of a “natural” mummy is the 5,300-year-old Ice Man of the Alps, a European traveler and metal-worker who froze to death in the high mountains.

The oldest mummies of which we have knowledge sprang from the Chinchorro people of coastal Peru. The hunter-gatherer Chinchorro, settling by the coast with its rich ecosystem, placed their dead flat on their backs in the nearby Atacama desert. The Atacama is perhaps the dryest place on Earth, and natural mummies have been found there from as long ago as 8000 BCE. Beginning about 5000 BCE the Chinchorro practiced artificial mummification, dismantling the body then remolding it wtih such strengthening agents as sticks, reeds, paste, and sea lion skin. For the next 6,500 years various peoples of Chile, Peru, Columbia, Ecuador, and the Andes practiced mummification techniques. The Inca sometimes mummified their human sacrifices (usually children). They worshipped the mummy of their king, “feeding” him and carrying him about on ceremonial occasions. In the 1500s CE the Conquistadors stamped out the practice of mummification, destroying all the mummies they could find.

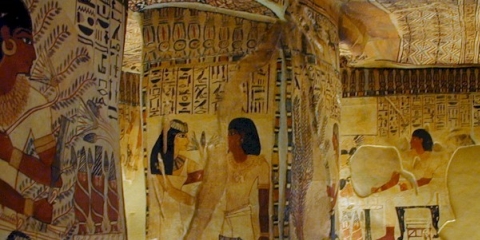

The best-known mummy-making culture is of course that of ancient Egypt.

Three recent books throw fascinating light on the state of the art in mummy studies. In In Search of the Immortals, anthropologist/filmmaker Howard Reid takes us on a geographical journey in search of the major mummy-making cultures. He begins in the Taklamakan desert of western China, site of a series of spectacular mummy discoveries, including the beautiful woman found by He Dexiu. A controversial result of these discoveries is substantial evidence that ethnic-European nomads were peopling the Taklamakan from as early as 1800 BCE.

Reid then takes us to the “ice mummies” of Siberia, then the “bog people” of Western Europe. The acidity of bogs and the lack of oxygen at deep levels has acted as an extraordinary preservative, so much so that on several occasions police have been called for a murder investigation on what turned out to be 2,000-year-old bodies! Many of these bog-people bodies died by violence, often multiple kinds of violence, including hanging, blows to the head, and cut throats. Reid speculates that they may have been criminals, executed war captives, voluntary ritual sacrifices, or a combination thereof. He goes on to Egypt, then to the Canary Islands, where he presents a strong body of circumstantial evidence, including mummification and pyramids, to suggest that the Guanche people of the islands bore the influence of Egyptian culture—probably by way of North Africa—right up to the Spanish incursions of the 1400s. Reid concludes with a detailed look at the mummy-making cultures of South America.

In The Mummy Congress, archaeology journalist Heather Pringle travels to the third World Congress on Mummies, held in Chile on the edge of the Atacama desert, where she learns that serious study of mummies is a passion, more often money-losing than mummy-making for mummy scholars. Caught up in mummy fever herself, Pringle writes, in good journalistic fashion, about various mummy issues. She looks at the fierce controversy among money professionals over whether to dissect mummies or study them through non-invasive technologies respectful of what are, after all, human bodies. She looks at the value of mummies in studying the evolution of mummies over time. She looks at mummy research into ancient drug use, the murder mysteries of the bog people, the mysterious European invaders of the Taklamakan, and the various commercial uses to which mummies have been put, and other more recent issues that will be referred to in my next article.

The Mummy in Fact, Fiction and Film by Susan D. Cowie and Tom Johnson is a book that every reader of this site should own. I’ll refer to it repeatedly in this series. Cowie and Johnson begin with a brisk but authoritative look at mummification around the world, including those cultures already mentioned as well as the natural-drying methods used by Australian aborignes and North American Indians. Then they turn to a detailed consideration of Eygpt.

To be Continued....

Sources: Howard Reid, In Search of the Immortals: Mummies,Death and the Afterlife, 1999; Heather Pringle, The Mummy Congress: Science, Obsession, and the Everlasting Dead, 2001; Susan D. Cowie & Tom Johnson, The Mummy in Fact, Fiction and Film, 2002; Nova, Mysterious Mummies of China [Video], 1998.