All About the Movies: A Selection of Non-Fiction Books About the Horror Film Genre

If you’re going to write non-fiction, and you don’t know everything, you’d better know where to look it up. (And when you find it, you’d better not quote too much of it without attribution.)

You can get a lot of good movie information on the Internet, particularly on the Internet Movie Database; you can also get plenty of information, misinformation and uneducated opinion on other sites. Meanwhile, some of us still look to our own reference libraries for convenience, credibility and depth.

I don’t have the biggest cinema library around by any means, but I do a lot of scouting in the used-book field, and I make a point of buying books on horror, SF and other genre films when they turn up. These range from critical essays to star biographies to uninformative collections of “stills.” Some are obviously more useful than others; the most useful books, day to day, are the movie guides or surveys. There are a number of competing books in this vein, no single “definitive” guide but an array of books with varied perspectives. I thought it would be fun and possibly instructive to write a guide, or survey, to movie guides—not a comprehensive survey by any means, but a look at the books on my own shelves.

General movie guides

Leonard Maltin’s Movie & Video Guide edited by Leonard Maltin (Signet Books, paperback, current edition $8.99)

This is the first guide to movies I ever purchased, back in the 1980s, when I still had one of those heavyweight top-loading VCRs, and it’s still the first guide I consult for a terse assessment of a run-of-the-mill movie. It’s thick as a brick, pleasantly styled, and updated annually. I think it represents the opinions of mainstream critics fairly accurately, and I tend to agree with Maltin most of the time on most movies, except some genre movies. It’s certainly not as friendly to horror and SF as it could be, despite the presence of Bill Warren, author of Keep Watching the Skies, on the editorial staff. On a four-star scale, The Shining gets two stars, The Evil Dead gets two and a half, Blade Runner gets only one and a half, and so forth. A good book to start a reference library, if you’re a general movie buff, but certainly not the only guide you’ll need if you’re a horror fan.

* * *

VideoHound’s Golden Movie Retriever by various eds. (Gale Group, paperback, current edition $24.95)

Another general guide, with some quirks and attitude, and a little more affinity for horror and SF than Maltin. You may in fact want to start your library with this book as a Maltin alternative. Also thick, terse and updated annually. Unfortunately it only covers movies on home video, not out-of-print movies that may turn up on TV. And it’s physically big and hard to handle. Notable for its humongous cross-indexing section, which I suppose is being supplanted by the Internet Movie Database.

Horror movie guides

Creature Features: The Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Movie Guide by John Stanley (Berkley Boulevard Books, 2000, paperback, $12)

Creature Features: The Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Movie Guide by John Stanley (Berkley Boulevard Books, 2000, paperback, $12)

This book is the closest thing to a one-volume genre fan’s guide as you can get. Stanley reviews everything from the Alec Guinness comic fantasy The Man in the White Suit to the artsy Man Who Fell to Earth to the gore-drenched Maniac, assessing each film on its own terms. He treats classic horror with reverence but also has fun with current action-SF. He covers more obscure flicks than his rivals and ventures into mainstream films with fantastic elements. Here are foreign films, silent films, animated features. I particularly value his coverage of old serials, not found elsewhere. A valuable book to keep next to your favorite TV-watching chair, with one big flaw: Stanley seems oblivious to misogyny, even in horror films where it is rampant (John Carpenter’s Vampires, for example). The minor flaws: running times aren’t listed, recent films get more ink than older ones even when they’re mediocre, and Stanley is prone to bad punning. Film fans who share this site’s advocacy of classic horror might find Stanley too generous to “slasher” films, but apart from occasional lapses, his opinions are generally in line with most fans I encounter. This was a pioneering guide when it was first published in 1981, a prehistoric year for home video. The evidence of its success is that it’s currently in its sixth edition as of August 2000.

* * *

VideoHound’s Horror Show by Mike Mayo (Visible Ink Press, 1998, softcover, $17.95)

VideoHound’s Horror Show by Mike Mayo (Visible Ink Press, 1998, softcover, $17.95)

You might expect this to be as comprehensive in its genre as the Retriever is for home video movies, but it turns out to be an idiosyncratic selection of films assessed by a quirky reviewer. Mayo is a horror imperialist, dragging unlikely films such as Natural Born Killers, The Bride With White Hair and Trainspotting into his overly loose definition of the genre, I suppose mainly because he likes these movies and wants to write about them. He also goes out of his way to play the iconoclast, calling The Bride of Frankenstein an “uneven film filled with dated humor,” arguing that the original The Haunting is “seriously flawed,” and so forth. Well-written and challenging, peppered with evocative stills, and supplemented by fine short essays on actors, studios, directors and eras, this guide is nevertheless just one critic’s somewhat off-beat take on the genre. In terms of value for the money, it’s too limited with only 999 films reviewed, and it’s a selection that doesn’t stick to the needs and tastes of its target audience. Published in 1998 and hasn’t been updated since. (FYI, VideoHound has also published similar guides to vampire films, “Cult Flicks and Trash Pics,” and what the publishers call “sci-fi.”)

* * *

The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Horror edited by Phil Hardy (The Overlook Press, 1994, hardcover and softcover, out of print)

The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Horror edited by Phil Hardy (The Overlook Press, 1994, hardcover and softcover, out of print)

If Creature Features is the unabashed fan among horror guides, the Overlook Encyclopedia is the skeptical academic. It’s both closely focused and as comprehensive as one could wish, covering a host of foreign movies and little indie obscurities. It also comes off as sort of snooty. For example: “The real problem, though, as with so many films of this type, is that no real distance is ever taken from the killer’s scrambled perceptions and that the film ultimately condones a world view which it purports to condemn as lunatic.” This highfalutin’ noise is addressing The Toolbox Murders, not a movie designed to stand up to that level of analysis. Most of the time, in fact, the capsule reviews in this book sound like the writers are slumming. But for all their latinate phraseology and post-modern detachment, the Overlook critics are usually predictable: they tend to dote on art-house horror, dismiss popular shockers, and give everything else a bemused pat on the head. You get this book, if you can afford it, not for a quick review of a movie in hand, but for its depth of knowledge of the international horror movie scene (though recent Asian horrors aren’t covered to any extent) and some insights that will feed debate. Incidentally, the book is arranged in chronological order, which is handy for some purposes, but if you don’t recall the release dates of movies you’ll be referring frequently to the fine-print index. It’s a big oversized tome, available in hardcover and softcover.

Horror guides with an agenda

The Essential Monster Movie Guide by Stephen Jones (Billboard Books, 2000, paperback, $19.95)

The Essential Monster Movie Guide by Stephen Jones (Billboard Books, 2000, paperback, $19.95)

Packaged in an apparent attempt to confuse buyers looking for a general horror guide, this book is much more specialized than that; it’s an attempt to chronicle every appearance by a “classic era” monster in movies, TV series or home video. So, you won’t find Psycho or even Rosemary’s Baby in this guide, because those fine movies don’t contain vampires, werewolves, Frankenstein creatures, zombies, stop-motion giant gorillas, or whatnot. Jones doesn’t review Halloween, but he does review Halloween II because that film features a few minutes of Night of the Living Dead seen on TV. The result is useful only to fans of the most obsessive kind. Want a list of the episodes of Happy Days or Roseanne with monster appearances? Did you know that, in Fellini’s City of Women, Marcello Mastroianni makes whoopee with a woman wearing a Frankenstein mask? Does it matter? This book has a five-star rating system, like a general viewer’s guide, but so many one- and two-star films are included, you find yourself wading through the pages looking for something Jones considers good. And readers might take issue with Jones’s ratings criteria for the better films. The original silent Nosferatu gets two and a half stars and From Dusk Till Dawn gets three and a half? (Video documentaries almost always seem to get decent ratings, making one wonder if Jones prefers documentaries on horror movies to the movies themselves.) The book does have a lengthy dose of Forrest Ackerman prose in its introduction, which can’t be bad, along with some cool photos from the Ackermansion archives, and it has what looks like a good bibliography. But overall, Jones, a talented writer and respected editor of horror anthologies, has produced a book that is an exercise in fannish completism, not a particularly useful viewer’s resource.

* * *

The Modern Horror Film by John McCarty (Citadel Press, 1990, paperback, out of print)

The Modern Horror Film by John McCarty (Citadel Press, 1990, paperback, out of print)

I haven’t spent as much time with this book as with some of the other guides, but it looks to me like the usual quality product from McCarty, author of The Official Splatter Movie Guide, The Fearmakers, and an intriguing guide to Thrillers, among other books. This is another volume in McCarty’s continuing effort to bring recent horror films under more serious scrutiny, to move beyond the fannish celebration of gore. As the introduction indicates, this book was written in reaction to then-current canonization of the “classic era” of horror, beginning in the silent era and petering out in the 1940s for purists or the mid-’50s for more liberal critics. Seems odd that as late as 1990, when this book was published, some critics would still dismiss any fright film made after 1957, snubbing Hammer, dissing Hitchcock and Polanski, turning up noses at Corman, Romero, Craven, Raimi, Barker, et al. McCarty argues for a new pantheon of “classics” made in the 30 years since Hammer Studios’ first venture in the genre, The Curse of Frankenstein. Seen from a decade’s distance, McCarty’s selections are a mix of recognized masterpieces (Curse of the Demon, Psycho, Rosemary’s Baby, Night of the Living Dead, etc.), and lesser but acceptable choices. A goodly number of Hammer films are represented—I count 12 of the 50—but McCarty is eclectic, with equal appreciation for furtive ghosts and axe-wielding psychos. Sometimes he casts his net wider than necessary, however, bringing in a couple of Sherlock Holmes films (Hammer’s The Hound of the Baskervilles and the Holmes-vs-Ripper film Murder By Decree), and some arty things such as The Devils and Altered States. And some fans will be dismayed at the absence of foreign language films. Even if you have trouble accepting the 1971 Macbeth or The Witches of Eastwick as horror classics, McCarty does set a nice buffet of interesting viewing, with a few surprises and subjects for debate. This book is unfortunately out of print, but it isn’t rare.

* * *

Nightwalkers: Gothic Horror Movies of the Modern Era by Bruce Lanier Wright (Taylor Publishing Co., 1995, paperback, $17.95)

Nightwalkers: Gothic Horror Movies of the Modern Era by Bruce Lanier Wright (Taylor Publishing Co., 1995, paperback, $17.95)

“Nightwalkers?” Well, I suppose they had to call it something. The title doesn’t quite convey the purpose of this book: to trace the lineage of classically styled horror films made between 1965–1976. These are movies haunted by classic monsters such as vampires, ghosts, werewolves and mummies, movies about the various incarnations of Frankenstein, movies about witches and Satanists, movies inspired by Poe and Lovecraft. It’s an attempt to separate “gothic” films from the mass of ill-defined horror cinema that encompasses gore flicks, suspensers and psychological shockers. Naturally much of Hammer Studio output is reviewed (the author is a Brit) but a number of other films less covered elsewhere are given their due here. The book is set up in the form of a viewer’s guide, complete with ratings (up to four skulls). A laudable effort, written in a friendly fashion and pleasingly designed. For fans of fright films who favor story and character over blood and guts, this could be the definitive rated guide to its period. However, it’s badly in need of an update or supplement. Only a few high-profile films later than 1976 are mentioned, and since it was published we’ve seen a revival of the gothic under the commercial label “supernatural thriller.”

* * *

Nightmare Movies: A Critical Guide to Contemporary Horror Films by Kim Newman (Harmony Books, 1988, paperback, out of print)

Nightmare Movies: A Critical Guide to Contemporary Horror Films by Kim Newman (Harmony Books, 1988, paperback, out of print)

Novelist and critic Newman, one of the contributors to the Overlook encyclopedia, wrote this opinionated essay between 1983 and 1988, more than a decade after the last serious horror histories had been published. It was one of the first books to look at the era of Hammer and thereafter with respect. Well, at least the good ones are treated with respect. Newman has the courage of his convictions in that regard. He’ll give some space to The Amityville Horror and The Omen, unavoidable box-office landmarks in the mainstreaming of horror, but he reserves his favor for more interesting, off-beat works such as the films of Larry Cohen and David Cronenberg. Not that he’s always consistent. He laments the “stereotypes, obscurities and muddy thinking” under the surface of the stunning visual effects and psychosexual symbolism of Alien, while praising Suspiria as “brilliant” for its style despite a cast of cardboard figures and a plot laden with absurdities. Yes, he’s eclectic and international, but he discusses only selected films in depth, content to mention or name-drop movies he considers minor. A book well worth reading in any case, for an intelligent writer’s take on post-classic horror, though it’s not arranged as a viewer’s guide, and if you try to use it that way you’ll be turning frequently to the messy index.

Pre-video horror guides

A Pictorial History of Horror Movies by Denis Gifford (Hamlyn, 1973, hardcover, out of print)

A Pictorial History of Horror Movies by Denis Gifford (Hamlyn, 1973, hardcover, out of print)

Before VCRs became standard household equipment, a few horror movie guides were written for those fans lucky enough to live near revival movie houses or devoted enough to stay up late and watch old flicks on TV. In the 1960s there were An Illustrated History of the Horror Film by Carlos Clarens and Horror in the Cinema by Ivan Butler; in 1973 came Gifford’s Pictorial History, an oft-reprinted oversized book which today seems to be the most common of its kind in the second-hand market. This is one of those books that created the generation gap for younger horror critics writing in the 1980s. Gifford gushes with nostalgia-tinged joy about the monster movies of the 1930s, sniffs at the sequels of the 1940s and completely dismisses Hammer films as exercises in sensational bloodiness (how things do change). The book is suffused with the spirit of Ackerman, mimicking but never approaching his colorful prose, and showcasing plenty of outsized “stills,” a book design feature that’s far less impressive in these days of DVDs. Gifford is worth picking up as an artifact, or a peek into horror fandom of days gone by, but not terribly useful anymore as a guidebook.

* * *

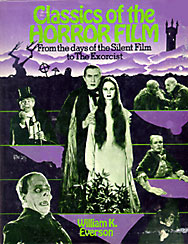

Classics of the Horror Film by William K. Everson (Citadel Press, 1974, hardcover, reprinted in 1990 as a $17.95 paperback, both editions out of print)

Classics of the Horror Film by William K. Everson (Citadel Press, 1974, hardcover, reprinted in 1990 as a $17.95 paperback, both editions out of print)

You’ve got to hand it to those guys who wrote about cinema before the availability of home video. I did a little of that kind of criticism back then, trying to report fairly and accurately on a film I could only view once or twice in a darkened theater, fumbling with a notebook, pen and tiny flashlight, and with only my own meager reference library for background information. No wonder you see a lot of factual errors and ill-considered judgments in pre-1980 writing about films. Everson, I’ve found, is one of the sticklers for accuracy among genre critics of that era, and a tasteful connoisseur as well. His Classics of the Horror Film is not the most common book on classic horror but it’s the most useful to today’s readers, in my opinion. Films Everson considers major are treated in separate, in-depth chapters, remarkable for their detail; other sections are surveys of movies with particular monsters or themes. Everson’s observations are carefully made and his background anecdotes well chosen. Of course, being a product of its time, this book snubs nearly all horrors made after the big-studio era, and modern readers may find Everson’s prejudice against color films amusing.