The Curse of Frankenfood

Ever since Mary Shelley’s baron rolled his improved human out of the lab, scientists have been bringing just such good things to life....If they want to sell us Frankenfood, perhaps it’s time to gather the villagers, light some torches and head to the castle.

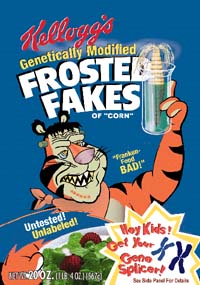

This passage, from a letter to the editor written by Boston College English professor Paul Lewis and published in the New York Times in 1992, has been credited with coining the phrase “Frankenfood” to describe genetically-engineered foods. For those of you who have missed all the hubbub relating to GMOs (genetically-modified organisms), this new technology relies on microbiology rather than breeding to affect change. Strands of DNA are inserted into the nuclei of an unrelated cell, creating an organism that shares the quality of the DNA strand as well as the original cell. The new “Golden Rice,” for example, is basmati rice that has been injected with a DNA strand from a daffodil, producing a grain of rice that is both high in vitamin A (beta carotene, the substance which gives daffodils their color) and yellow in appearance (hence, “Golden”).

This, of course, is the stuff of science fiction. Then again, so is Frankenstein.

Although references to Frankenstein are being bandied about with glee, it’s clear that neither camp really understands the complexities of the story of Dr. Frankenstein and his monster. People who embrace the promise of technology resent the association of GM food with the monster. The creature, they say, symbolizes science run amok, and engendering such fear only slows the development of what might one day be life-saving technologies. Those who oppose the development of biotechnology see the image of the Frankenstein monster as a warning, painting the scientists who work to achieve such technological “monstrosities” as, if not mad, greedy beyond compare. Somewhere in between are those of us who were raised on classic horror.

Although references to Frankenstein are being bandied about with glee, it’s clear that neither camp really understands the complexities of the story of Dr. Frankenstein and his monster. People who embrace the promise of technology resent the association of GM food with the monster. The creature, they say, symbolizes science run amok, and engendering such fear only slows the development of what might one day be life-saving technologies. Those who oppose the development of biotechnology see the image of the Frankenstein monster as a warning, painting the scientists who work to achieve such technological “monstrosities” as, if not mad, greedy beyond compare. Somewhere in between are those of us who were raised on classic horror.

Fans of classic horror will tell you that there are no angry villagers in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The villagers didn’t show up until James Whale’s film version in 1931—a classic in its own right, but a far cry from Shelley’s novel. And while Whale’s villagers did storm the castle, it was fear—not wisdom nor conscientious objection—that drove them to act.

The scientist, our dear Dr. Frankenstein, fares no better. His drive, whatever its source, amounts to this: the ends justify the means. Ethical concerns are secondary to his desire to cheat death, despite the fact that the “ends” for which he is striving are still unclear, undefined, untested. What Dr. Frankenstein (Henry, Whale’s film version of the infamous doctor, as opposed to Victor, Shelley’s creation) does do is pave the way for generations of monster movie scientists whose pursuits are less ideal, beginning with a rather megalomaniacal, although thoroughly entertaining, Dr. Pretorious in Whale’s 1936 opus, Bride of Frankenstein.

Those of us who grew up with Frankenstein (and here I mean the monster, as portrayed first by Boris Karloff, and followed by many others, most notably Bela Lugosi and Glenn Strange) sympathize with the monster, a forlorn creature brought into this world not by choice nor by action. He stumbles along, managing as best as he can, as many of us did through our childhoods and early adulthoods. We knew the monster intuitively, responded to him compassionately. We wanted for him to survive, to be loved and cared for by, if not those who created him, those who found him and learned to love and understand him.

Of course, not every Frankenstein film monster is worthy of our compassion or understanding, nor is every Frankenstein film the caliber of Whale’s dynamic and innovative work. Just as Dr. Frankenstein and his imitators in film became more and more single-minded and cruel—as well as camp—in their pursuits, so did the monster become less endearing, more threatening, more unpredictable and therefore dangerous. This is the stuff of genre film-making.

This isn’t to say there’s nothing to learn from generations of Frankenstein films. The truth is, no matter how far apart in skill or execution, even the least of the Frankenstein films has something in common with its literary progenitor, and even the least of these films, along with its forebear, has something to offer to the discussion on genetically-modified organisms.

A very young Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein in the year spanning 1816-17. She was the daughter of two prominent social reformists, her father a stern and distant man, and her mother an advocate of women’s rights who died while giving birth to her. She spent the summer of 1816 in a home on the shores of Lake Geneva with her lover (and soon to be husband) Percy Bysche Shelley and his good friend the infamous British outcast George Lord Byron. A wet and rainy year, the three, along with Byron’s personal physician John Polidori, spent much of their time indoors. One evening, bored and looking for entertainment, Byron suggested that they indulge in a little friendly competition: each of them would write a story. A horror story. At first, Mary found it somewhat difficult. And then one evening she had a dream of a scientist who gave life to a dead body. The dream frightened her, and in retelling it found the inspiration for one of the greatest horror stories ever told.

While there is magic in any act of artistic creation, all art is influenced by its context, and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is no different. Written in the midst of the Enlightenment, Frankenstein is a product of its time. The Enlightenment posited the central place of “man” in the universe, the possibility of progress, and the ability to solve the mysteries of the universe through scientific inquiry. Major scientific discoveries were being made, discoveries that would forever change our perceptions of the physical world.

The success of the scientific method and empiricism as tools for answering questions about the mysteries of life contributed to the breakdown of faith and a deepening fascination with the elusive boundaries between life and death. In the 1790s, Italian physician Luigi Galvini had discovered that electrical impulses could cause the muscles of dead frogs to twitch, suggesting that perhaps electricity could restore the dead to life.

This and other scientific advances gave a feeling of stark reality to Shelley’s vision of a scientist who collected the parts of the recently dead and reconstructed a man “in his own image” and presumed to put himself on equal footing with God. Given the audacity of Dr. Frankenstein, it’s rather easy to summarize Frankenstein as a critique of science and scientific pursuits, but many critics have deconstructed Frankenstein and have come up with other equally compelling assessments of the story Mary Shelley had to tell.

Some have said that Frankenstein is a tale of bad parenting, the “father” neglecting the son. Others have read Frankenstein as a story written by a mother who continually grieved the loss of her own young children (in all, Mary would lose 4 of her 5 children). Still others have seen in Frankenstein the condemnation of a man who assumes the role of God in the creation of life—a story that warns against the scientific community presuming to control nature. It is this reading that fuels the analogy between Frankenstein and “Frankenfood.” Outspoken critics of genetically-modified organisms challenge the rights of scientists to tamper with “nature.” Scientists claim that the human race has “tampered” with nature since the first seed was sown and the first plant harvested by human hands.

Of course, “tampering with nature” is the theme that runs throughout all Frankenstein films, from James Whale’s 1932 classic to Frankenhooker and Frankenweenie. But at the core of each of these is a story of responsibility, whether a parent for a child, a mad doctor for his creation, or a boy for his dog. And this is where the “Frankenfood” analogy falls short.

If there’s a moral to be gleaned from the myriad versions of Frankenstein, it’s that actions have consequences, and that we should seriously consider the consequences before charging full-steam ahead. After all, Victor Frankenstein, as written by Mary Shelley, is far from mad and I doubt Mary Shelley saw the monster as inherently dangerous, despite her description of him as ugly and thoroughly distasteful in appearance. A misbegotten creation of an overzealous scientist, the monster suffered more from neglect and abandonment than any desire to cause harm.

As scientists, politicians and policy makers barge ahead with the commercialization of genetically-modified organisms, as critics decry GMOs as risky, and both rely on reducing the arguments to a rather simplistic reading on one of our culture’s most enduring tales, I can’t help but wonder if it’s not about time for everyone to actually read the book. Or at least watch the movie.

* * *