Vampire Over London: Bela Lugosi in Britain

The eyes of men were blinded because of their inequities and the hardness of their hearts....And on the seventh day, the sun shone in the heavens, giving light on mountains and on valleys, on rivers and the multitudinous sea. And they who were blind did see again.

Bela Lugosi delivered the above sermon, one of only two he made on film, in 1939’s Dark Eyes of London, his second British movie. Though Lugosi’s character, the blind Rev. John Dearborn, is later revealed as a mad killer, his pious words capture the work behind our new book, Vampire Over London: Bela Lugosi in Britain.

Vampire Over London tells for the first time the story of the legendary stage and screen Dracula’s final performances in the role that made him immortal. The fable of Lugosi’s last stage tour in Dracula in 1951, as repeated in his various biographies, ignored the few facts and evidence available. Shortly into our work, we realized that virtually everything published about the 1951 Dracula, was incorrect. We “who were blind did see again” as we slowly uncovered and documented the truth.

Misconceptions of Lugosi in 1951—that the Dracula tour flopped and closed after a few performances; that Bela and his wife Lillian were left stranded in England until a role in a low budget film gave them the cash to return home—have gained wide acceptance over the past 25 years. In the early 1990s, we began collecting evidence and recollections of Lugosi in 1951. The truth was soon revealed in British newspaper archives, particularly in the pages of The Stage, the trade journal of British theatre. Contrary to popular myth,Dracula ran 221 performances from April to October 1951, in 22 cities. Our letters to newspapers and radio talk shows where Dracula appeared brought dozens of responses from persons who had seen Lugosi perform. Some of them had met Bela during his week in their hometowns. Over the years, we located many of the surviving members of the Dracula company. Their stories all agree. Dracula had a fine run in the provinces, and failed only in that it never reached London’s West End, the central theatre district. And the Dracula company all agree on Bela—an admired and respected co-worker and a warm, beloved friend.

In our research, we found dozens of forgotten reviews of Dracula and tracked the Lugosis across Britain through local newspapers. Audiences and critics often found the play itself a creaking melodrama, but Lugosi himself drew almost universal praise. The true story of 1951, told for the first time in our new book, reveals Lugosi’s valiant, persistent struggle against changing public tastes and his own failing health.

§

As 1951 dawned, Lugosi’s career stood at a low ebb. For a generation, he had been trapped in the stereotype of Count Dracula. In Hollywood, gothic horror was distinctly passé. Any rumblings of a horror revival were transformed into the birth of the modern science fiction genre. Bela Lugosi, like his fellow horror stars Boris Karloff and Lon Chaney, saw scant demand for his services. Since the late 1940s, Lugosi had mainly worked out of New York, taking whatever jobs he could find. He guest-starred in repertory productions of Dracula and Arsenic & Old Lace, and made a few television and radio appearances. Too often the only work available were dreaded personal appearances in vaudeville horror & magic shows. By 1951 even these were drying up. Lugosi was offered a chance at a comeback when his friend and agent, Richard Gordon, negotiated his appearance in a new stage production ofDracula. The plan called for a brief theatre tour of the British provinces before a run in London’s West End. Bela and Lillian sailed from New York, and arrived in London on April 10.

As 1951 dawned, Lugosi’s career stood at a low ebb. For a generation, he had been trapped in the stereotype of Count Dracula. In Hollywood, gothic horror was distinctly passé. Any rumblings of a horror revival were transformed into the birth of the modern science fiction genre. Bela Lugosi, like his fellow horror stars Boris Karloff and Lon Chaney, saw scant demand for his services. Since the late 1940s, Lugosi had mainly worked out of New York, taking whatever jobs he could find. He guest-starred in repertory productions of Dracula and Arsenic & Old Lace, and made a few television and radio appearances. Too often the only work available were dreaded personal appearances in vaudeville horror & magic shows. By 1951 even these were drying up. Lugosi was offered a chance at a comeback when his friend and agent, Richard Gordon, negotiated his appearance in a new stage production ofDracula. The plan called for a brief theatre tour of the British provinces before a run in London’s West End. Bela and Lillian sailed from New York, and arrived in London on April 10.

The Lugosis did not find, as had so often been claimed, an under-funded production stocked with amateur performers and run by inexperienced entrepreneurs. Actually, the cast were seasoned performers. Even the youngest of them, 21-year-old leading lady Sheila Wynn, had 8 years of professional experience. Richard Eastham, though only in his early 30s, had already directed Laurence Olivier and John Gielgud. He had been in theatre his whole life and, as a boy, he had seen Dracula performed by Hamilton Deane’s company.

When producer John Mather initially met Bela, he was immediately concerned about the aged actor’s stamina. Bela, on first appearance, seemed stooped and feeble. His complexion looked most unhealthy, and he obviously depended on the always present Lillian simply to get through each day. During the early rehearsals Lugosi mumbled his lines and seemed in a hurry to get through his scenes. Mather considered cancelling the tour at the outset, but all worries vanished when Bela went through his part in character. He stood erect and expanded his chest; a magnificent voice and presence filled the rehearsal hall. “He looks 40 again,” thought Mather (himself only 28). What most impressed the producer was the twinkle in Bela’s eye, and the gaze that could electrify an audience. At one moment Lugosi’s Dracula was the nice old count who lived next door—in a flash he became the devil himself. Mather was sure he had a winner.

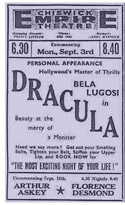

Dracula opened in Brighton on April 30, less than three weeks after the Lugosis arrival. Reviews from the local newspapers and from The Stage were quite favorable. As the tour played through towns across Britain and in the outer boroughs of London, Mather worked to find his production a slot in the West End, the central London theatre district. His strategy was always to tour Dracula for a few months and then bring it to the West End. With the burden of Lugosi’s star salary (about $1,000 a week, 10 times greater than the next highest paid cast member), Dracula could do little more than break even on the road. Mather had built a war chest, and was prepared to keep the tour going through all of 1951 if necessary, until the West End beckoned.

Gothic horror was no more in vogue in London than it was in Hollywood, and West End booking agents gave Mather a chilly reception as he pitched Dracula to them. Those agents were not inclined to take risks. The troubled post-war British economy was particularly hard on theatres, as was the advent of television. Across the Thames, the Festival of Britain—a World’s Fair type extravaganza designed to snap Britain out of the post-war doldrums—drew up to 50,000 people a day. A lot of those patrons, thought the West End theatres, came at their expense. Like Hollywood and Broadway, they fought to survive with what was considered the taste of the day, modern realistic drama and sophisticated comedy. A play with an air of nostalgia, like Dracula, held no interest for them. Still, buoyed by the generally positive reviews that Dracula was earning in the provinces, Mather did not relent. He never doubted that he could sell Dracula on the West End, and was prepared to wait.

§

Outside of the West End, Dracula had no problem with bookings. Many of its engagements were in music halls, with twice-nightly performances, usually at 6:00 and 8:30. Music hall audiences were not reverential of the great Lugosi or any other performer, and many towns throughout England prided themselves on their reputations for giving visiting artists a rough time. Applause and jeers from these houses might come at odd times during performances. Lugosi, a past master at working a crowd, quickly learned to deal with this new type of patron. Whether he played in the neighborhood halls (where Dracula did 12 performances per week) or in the grand theatres of the Victorian age (usually only 7 or 8 performances weekly), he consistently garnered rave reviews. Particularly memorable was his closing speech after the curtain calls:

Outside of the West End, Dracula had no problem with bookings. Many of its engagements were in music halls, with twice-nightly performances, usually at 6:00 and 8:30. Music hall audiences were not reverential of the great Lugosi or any other performer, and many towns throughout England prided themselves on their reputations for giving visiting artists a rough time. Applause and jeers from these houses might come at odd times during performances. Lugosi, a past master at working a crowd, quickly learned to deal with this new type of patron. Whether he played in the neighborhood halls (where Dracula did 12 performances per week) or in the grand theatres of the Victorian age (usually only 7 or 8 performances weekly), he consistently garnered rave reviews. Particularly memorable was his closing speech after the curtain calls:

Just a moment, Ladies and Gentlemen! Just a word before you go. We hope the memories of Dracula and Renfield won’t give you bad dreams, so just a word of reassurance. When you get home tonight and the lights have been turned out and you are afraid to look behind the curtains and you dread to see a face appear at the window...why, just pull yourself together and remember that after all thereare such things.

Traditionally, the monologue is given by the actor playing Van Helsing—a practice that began with the original Van Helsing, Hamilton Deane, who also wrote and produced the first dramatization of Dracula. In the late 1940s in the United States, where Lugosi’s appearances in Dracula were as guest-star of a repertory troupe, he took over the curtain speech. When he proposed doing it for the 1951 tour, Richard Eastham immediately agreed, as he wanted to give the audience as much Bela Lugosi as possible. Depending on the theatre, the effect of the closing monologue was augmented by special effects. As Lugosi spoke, fog would pour from beneath the curtain. Once, in Wood Green, the smoke rose to engulf Lugosi, who vanished as his cape fell to the floor. His demonic laughter then filled the house. At least once, he reappeared after the “final” exit and snickered, “Are you afraid?” before vanishing for good. When he sensed the audience knew about the monologue and needed a jolt, the smoke might come early, as he said, “...and remember,” leaving them to fill in “there are such things.” Whether he played the closing speech tongue-in-cheek or with all the satanic power he could muster, he set the house roaring with applause.

To offer up a bit more of Bela Lugosi, Eastham added a prologue to the play. Sheila Wynn as Lucy Seward would stand in a trance-like pose between two large sheets of gauze. On the upstage sheet was a silhouette of large bat. Bela stood immediately behind it, his arms and cape outstretched in the same outline. Mist flowed across the stage, as a bat fluttered overhead. Sheila became increasingly terrified, screamed and ran off, as the curtain rose. The mist effect and especially the bat—a two-foot prop, which flapped its wings—were prone to mechanical problems. On the second week of the tour, the bat’s wires jammed, and it hung suspended at eye-level with the actors through the first scene. For the months to come, the bat would have recurring problems.

A simpler prologue—Bela simply arose from his coffin, stared imperiously into the house, and exited—soon replaced it. Though plagued by back and leg pains, the aging Lugosi could still rise with flourish from his coffin once or twice nightly onstage for the prologue. For the play’s finale, when Dracula is trapped in his coffin by Van Helsing and the vampire hunters, Lugosi was replaced by a prop dummy. He supplied Dracula’s death scream from the wings.

§

Except for brief forays into Scotland and Northern Ireland, the Dracula tour played mainly in the British Midlands and the suburbs of London. The original schedule, announced to the press and probably the one Bela and Lillian planned for, called for 10 weeks of touring before entering the West End. But the West End did not beckon. John Mather had a verbal agreement from his old employer, The Garrick Theatre, to take Dracula when its current offering, To Dorothy A Son (starring a very young Richard Attenborough) closed. Against all predictions, Attenborough’s play rolled on through the summer, and no other theatre yet showed any interest.

Except for brief forays into Scotland and Northern Ireland, the Dracula tour played mainly in the British Midlands and the suburbs of London. The original schedule, announced to the press and probably the one Bela and Lillian planned for, called for 10 weeks of touring before entering the West End. But the West End did not beckon. John Mather had a verbal agreement from his old employer, The Garrick Theatre, to take Dracula when its current offering, To Dorothy A Son (starring a very young Richard Attenborough) closed. Against all predictions, Attenborough’s play rolled on through the summer, and no other theatre yet showed any interest.

As week 10 of the tour neared, members of the Dracula company realized they were not “returning to London,” but only passing through before another five-week swing to the north. Several made plans to leave. Over the next few weeks, Dracula would see a new Van Helsing and Wells onstage, and new stage manager and assistant backstage. To minimize the drain on his bankroll, Mather did not fill the special effects manager’s job when Joan Harding left to become the new Wells. Sheila Wynn was offered a lead role in another touring production, but decided to stay with Dracula, as did David Dawson, Eric Lindsay and John Saunders (who played Seward, Renfield and Butterworth). Richard Butler left for two weeks for military reserve duty. Performances in Manchester in week 11 reflected the disheartened mood and shifting makeup of the company, and the reviews were the most disapproving of the tour. Within a few weeks, after Butler returned and the new company members settled in, morale revived, and Dracula again enjoyed fine reviews and audiences. Bela was further buoyed by the announcement in early August that he would co-star in Mother Riley Meets The Vampire. From New York, Richard Gordon had negotiated Lugosi’s appearance with George Minter, head of Renown Pictures. Filming was announced for October–November.

§

As Dracula continued its run in the provinces, John Mather persevered in fighting for a West End slot. The Ambassador and The Duke of York Theatres at last seemed interested in booking Dracula for the fall. The Garrick still wanted Dracula once To Dorothy A Son closed. Bela’s upcoming film role bothered Mather not at all, since many West End performers combined film work with their stage appearances (Bela had done exactly that in 1943, when he filmed Return of the Vampire during the day, while starring in a Los Angeles production of Arsenic & Old Lace at night). Finding a West End booking seemed only a matter of time and scheduling, but Mather did not appreciate the toll the tour was taking on his 68-year-old star. The schedule through the late summer was almost entirely two performances nightly, and Bela could scarcely recover his strength through the day to appear again each night. He made a handful of personal appearances in various towns, but usually spent all his spare time resting his delicate back and legs. When weary, he was most exposed to “lightning pains”—intense sciatic attacks through sent jolting surges through his lower body.

As Dracula continued its run in the provinces, John Mather persevered in fighting for a West End slot. The Ambassador and The Duke of York Theatres at last seemed interested in booking Dracula for the fall. The Garrick still wanted Dracula once To Dorothy A Son closed. Bela’s upcoming film role bothered Mather not at all, since many West End performers combined film work with their stage appearances (Bela had done exactly that in 1943, when he filmed Return of the Vampire during the day, while starring in a Los Angeles production of Arsenic & Old Lace at night). Finding a West End booking seemed only a matter of time and scheduling, but Mather did not appreciate the toll the tour was taking on his 68-year-old star. The schedule through the late summer was almost entirely two performances nightly, and Bela could scarcely recover his strength through the day to appear again each night. He made a handful of personal appearances in various towns, but usually spent all his spare time resting his delicate back and legs. When weary, he was most exposed to “lightning pains”—intense sciatic attacks through sent jolting surges through his lower body.

Mather was very conscious of Bela’s age and infirmities when they first met, but had learned over the months of the tour that onstage Bela was always a dynamic performer. The producer saw Dracula whenever it played near London, and knew that Bela never failed to mesmerize his audience. As Mather watched a performance in early September at Chiswick, neither he nor anyone else in the audience realized that lightning pains descended on Bela late in the performance, almost crippling him. At that moment, in the third act of the play in the only scene that Dracula shares with Renfield, Lugosi seized actor Eric Lindsay. The script called for Dracula to choke Renfield and throw him to the floor. Bela did exactly that—the only outlet for his silent scream was his death grip on his co-star. Offstage, Lindsay warned Bela never to handle him so roughly again, but the Renfield actor could no hold no grudge against a man he greatly admired. After months on tour, company members had few secrets from each other—the Dracula cast knew how Bela sometime suffered from attacks. And they knew he took morphine or methadone to deal with the pain.

After the performance, Mather visited Bela’s dressing room as he often did, bubbling with news of the West End’s new interest in Dracula. He did not notice that his star was trembling and soaked in perspiration. Lillian arrived. She and Mather cared little for each other; she did not acknowledge his presence. Lillian removed a small leather kit from her purse, rolled up Bela’s shirt sleeve and administered an injection. Mather watched in some disbelief and quickly left.

The tour continued, filming for Mother Riley Meets The Vampire neared, and still no slot on the West End. Mather travelled north from London to Derby to visit with his star. The only bookings he could manage for late September/early October were far-off in Newcastle. Could Bela go that far again? Lillian would have flatly told Mather no, that Bela would not suffer through yet another long trek to the chilly north—but she was not present. As John described the upcoming dates to Bela, the producer again realized how old and frail the actor was. Bela listened carefully, and stared at the young man for a long time. “John, I can’t go on. It’s taking too much out of me. Please finish it quickly.”

That Friday, a single sheet of paper posted outside the business manager’s office at the Derby Hippodrome announced that the Dracula tour would end in Portsmouth. The two weeks between Derby and Portsmouth were left open. Actor’s Equity rules required that the cast be paid for the empty weeks, and the company reassembled in Portsmouth with no defections. On Saturday night, October 13, 1951, the troupe gave its last two performances. Bela and Lillian could not know that he would never play Dracula again, but he had some inkling that his days of stage tours were over. Throughout the past six months, he had occasionally mentioned that he was glad to have “one last fling” at the role.

§

Lugosi’s last hurrah as Dracula was quickly forgotten. The movie he made before returning to America, Mother Riley Meets The Vampire, would not be seen in the United States for 12 years. Another decade would pass before serious interest in his life and career revived. By then, the only readily available records of his final Dracula were some garbled memories and a few tattered clippings of his first days in London after his arrival. The story of Lugosi’s farewell to his great role lie in British provincial newspapers and in the memories of his co-workers and audience members. These sources were entirely obscured from American-based Lugosi biographers, who reasonably concluded that the lack of information reflected a lack of any real activity. In time, the fable grew that the 1951 Dracula was a dismal failure that closed after a few performances, that the tour’s early collapse left the Lugosis stranded in England until the film role gave them the cash to return home.

Lugosi himself unwittingly played a role in clouding the full story of 1951. In his mind he failed in that his last Dracula never reached the West End. The Lugosis never mentioned their time in Britain after they returned.

Bela never found that last comeback, never was able to bring his special magic to London’s West End. But for six months, he ranged over Britain in unforgettable performances that were still vivid a half century later. Bela might have taken solace, if he had recalled his only other sermon on film, which ironically came in another of British films. In 1935’s Mystery of the Mary Celeste, Lugosi’s character Anton Lorenzen delivers the eulogy for a dead shipmate. Lugosi reads from Ecclesiastes:

I have seen the travails which God has given to the sons of Man. He has made everything beautiful in His time. Also, He has set the word in their hearts so that no man can find out the work that God maketh from the beginning to the end.

As Ecclesiastes warns, Bela never saw the grandeur of his final Dracula, and we are honored to tell the full tale for the first time.

§

The result of our researches is a new book, Vampire Over London: Bela Lugosi in Britain, (handbound, hardcover, 368 pages plus illustrations and dust jacket) published by Cult Movies Press. Only 1,000 copies exist. To obtain a copy, send a check for $29.95 plus $3.00 S&H (in the USA, Texas residents please add $2.48 sales tax) to:

Cult Movies Press

644 East 7½ Street

Houston, TX 77007

§