Conrad Veidt: Cinema’s Dark Prince, 1893-1943

Young Drifter

Conrad Veidt was born January 22, 1893 in a working-class neighborhood in Berlin, Germany. His father, Philipp, was a former military man turned civil servant. His son recalled, “Like many fathers, he was affectionately autocratic in his home life, strict, idealistic. He was almost fanatically conservative.” By contrast, his wife, Amalie, was sensitive and nurturing. The Veidts’ first son died in 1900. Hans Walter Conrad, the surviving child, became known as Conrad, familiarly Conny.

Conrad Veidt was very close to his mother, spending long afternoon hours, seated at her feet or rowing her in a boat in a park while she told true stories of her Berlin childhood, or “read wonderful fairy tales to me from a thick leatherbound book. My mother’s voice was as soft as velvet and her face seemed to light up as she read me these classic children’s stories.” He particularly remembered a magic day, when he was about eight, that his mother took him to downtown Berlin by horse-drawn streetcar, where they visited the zoo, went shopping, ate delicious food in a fashionable restaurant—and visited an early movie theater, where they saw two short films, primitive but enchanting.

Philipp Veidt hoped that his son would follow his footsteps into a military career. But Conrad was a dreamy lad, well-behaved at the Hohenzollern school but an inattentive student. “Whenever I rose from my school bench, lanky and thin and very hesitant, and began to stutter forth some nonsense from a book that interested me precious little, I was mostly greeted with laughs and derisive remarks from my schoolmates.” He was often picked on by other boys on the playground, though he defended himself. Despite his poor academics, Conrad for a time dreamed of becoming a doctor, after his father’s life was saved by a delicate operation.

Then in 1911 Conrad’s school decided to invite him to recite the prologue for the annual Christmas play. People told him that his clear, strong recital had been the best part of the play. Conrad finally acquired a serious goal: to become an actor.

Apprentice Actor

In 1912 Conrad graduated without diploma, 13th in a class of 13. But while he appeared to be drifting, he was actively studying his craft. With the money he raised from odd jobs andfrom the meager allowance his mother could afford, he attended Berlin’s many theaters, sitting or standing near the back of the gallery, “bewitched by the magic of the play transpiring on the stage below me.” He was especially taken with the productions in Berlin’s official Deutsches Theater, run by the legendary Max Reinhardt. In the late summer of 1912 a kindly doorman introduced Conrad Veidt to an associate of Reinhardt’s, Albert Blumenreich. Blumenreich was sufficiently impressed with the young man’s determination that when he learned he couldn’t afford the tuition for his evening acting classes, Blumenreich allowed Veidt to enroll for free.

Veidt recalled, “As a young man of 19 and 20, I was too tall and too thin. I had no flesh on mybones. My legs were always getting in the way. As for my hands, they were a terrible and constant problem. They dangled out of my sleeves, which seemed always too short.” But he gained poise from Blumenreich’s instructions, and after several weeks Blumenreich got Veidt an audition with Max Reinhardt himself. Veidt’s audition monologue—from Goethe’s Faust—impressed Reinhardt sufficiently that Veidt was enrolled in the Reinhardt stage training school. Better still, Veidt would be paid a modest salary of 50 marks a month for his studies!

Veidt’s mother supported his choice of profession, but his father angrily told him he was wasting his time. But if Conrad Veidt had it in him to be a successful actor, he could have chosen no more promising pathway than Reinhardt’s school. During his years as director of the German theater, Reinhardt trained a generation of actors, directors, and set designers, many of whom (including Veidt, Paul Wegener, Werner Krauss, F.W. Murnau, Ernst Lubitsch, Henrik Galeen, Paul Leni, and Marlene Dietrich) would also become active in films. Reinhardt also made innovative use of lighting, shadows, and smoke to suggest the emotional tone of scenes. At this time expressionism—a school of writing and art that eschewed realism, allowing the outer landscape to reflect inner thoughts and emotions—was drawing much attention in Germany. Reinhardt didn’t consider himself an expressionist, but expressionism became associated in people’s minds with Reinhardt, his Deutsches Theater, and his smaller Kammerspiele (“intimate theater”).

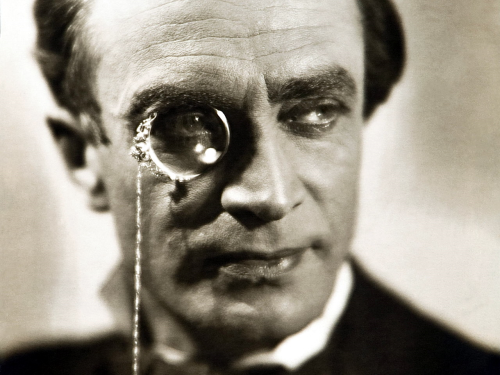

In 1913-1914 Veidt appeared on stage in several wordless cameos, gradually working his way up to tiny speaking roles. About this time he acquired the first of his trademark monocles. Veidt had poor eyesight in his right eye and, whereas he felt that glasses would hurt an actor’s image, he thought a monocle would lend distinction. As he gained in confidence, the gawky kid became a handsome, well-spoken charmer. He received perfumed notes from ladies in the audience, and became a popular escort for actresses.

In 1914 Veidt and actress Lucie Mannheim fell in love—but their romance and Veidt’s acting career were interrupted by WWI. Veidt was drafted, entering the German army in December. In May 1915 noncommissioned officer Veidt left for the Eastern Front, fighting for Warsaw against the Russians. Veidt contracted jaundice and pneumonia and was evacuated to a hospital by the Baltic Sea. While there, he got a letter from Lucie, working at a Front theater in Libau. Veidt applied to the theater, and it was decided that in his weak condition he could best serve the army by providing entertainment for the troops. The theater presented a different play every few days, providing Veidt with broad experience in both lead and supporting roles. But Lucie and Veidt found that the magic was no longer there between them.

In 1916 Veidt was reexamined, found medically unfit for further military duty, and honorably discharged. He applied to Reinhardt’s Deutsches Theater and was readmitted. In January 1917, back in Berlin, he played a priest in a small part that got him his first rave review, the reviewer hoping that “God would keep Veidt from the films.”

It was a busy period for Veidt between the plays and hanging out with his fellow actors in bistros after performances, though his enjoyment was marred that June by the death of his father, who, happy that his son had survived the war, had stopped complaining about his profession. If he had lived a bit longer, he could have seen his son become a star.

Films

German filmmakers produced several notable films in the ’teens, including such horror fantasies as actor/director Paul Wegener’s The Student of Prague (1913) and The Golem (1915). With the coming of war, Allied films were banned, increasing demand for home-made films. Film scouts regularly attended the Deutsches Theater, and in 1917, doubtless to the friendly critic’s disappointment, Veidt was recruited for films.

For the years 1917-1918 biographer Jerry C. Allen lists Veidt appearances in 26 stageplays and 18 films, and this is not necessarily a complete list! With his tall, lean frame (6'3", 165 pounds), his elegant bearing, his piercing eyes with their sometime-monocle, and his handsome but unusual face, he was often cast as a villain. Whatever the role assigned him, Veidt studied the craft of filmmaking with the same intense focus he had brought to stage acting, often questioning directors and cameramen about their work.

Veidt met actress Auguste Marie “Gussy” Holl at a party in March 1918. They took to each other immediately and were married that June. They went on to act together in six films. But as often happens with “love at first sight,” they soon realized they were incompatible. A trial separation led to divorce. Veidt, after succumbing to depression, threw himself into his work. It also seems likely that, like most of his fellow actors, he partook of the wild nightlife then flourishing in Berlin.

The war’s end in November 1918 and the establishment of the democratic Weimarr government produced a flood of creativity in German society. For about five years Germany produced, arguably, the most interesting body of films in the world. Inspired by unprecedented freedom of expression and by the angst attendant upon runaway inflation after the war, the filmmakers in those years often turned to dark-fantastic subjects. Especially notable were Wegener’s The Golem: How He Came into the World (1920) and F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922).

Veidt appeared in at least 15 films during 1919, including a version of Jules Verne’s novel Around the World in 80 Days, in which he starred as Phileas Fogg, and Peer Gynt, from Ibsen’s play, featuring Veidt as the supernatural Button Moulder. Different from the Others, part of a series of films about sexuality, was a brave plea for tolerance and understanding of homosexuals (the Nazis would later try, unsuccessfully, to destroy all prints). Veidt played a gay violinist threatened with blackmail over his sexual identity. Eerie Tales was an anthology of five tales (based on stories by Poe, Robert Louis Stevenson, et al.), with Veidt playing a different part (including Death) in each episode. Figures of the Night was a ghost story.

Also in 1919 Veidt and Murnau formed their own small studio, Murnau-Veidt Filmgesellchatt, for which Murnau would direct several films. The first was Satanas, featuring three stories, each from a different period, with Veidt playing the dual role of Satan and a different mortal character in each segment. Veidt himself directed two films for their studio, including Madness (1919), featuring Veidt as a banker obsessed with finding a trunk that a fortune teller has told him holds the key to the future.

Caligari and Fame

And, in 1919, Veidt was cast in the film that would make him an international star, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz sold producer Erich Pommer an offbeat screenplay, intended as an allegory of the German authority figures who had dragged a sleepwalking populace into war. Pommer, sensing the opportunity to make a distinctive film on a low budget, assigned the direction to Robert Wiene.

Caligari was the tale of an evil carnival magician, Dr. Caligari, who controls a somnambulist, sending him out to commit murders. The producer, director, and scriptwriters agreed that set designs using modern art would fit the strange story, and it also occurred to them that painted sets, complete with painted shadows, would save on lighting costs. Wiene assigned the set design to three expressionist artists; hired stage and screen veteran Werner Krauss as Caligari; and cast about for a new face to play Cesare the somnambulist. A crew member suggested Conrad Veidt. The film was completed in late 1919, released to underwhelming response, then re-released in February 1920 after a brilliant promotional campaign (Berlin was papered with billboards proclaiming “You will become Caligari!”)

Caligari was controversial on its German release, and grew more controversial on its American release in 1921. It is controversial still. Pommer and Wiene decided to change the story’s frame narration by Francis, the young hero (Friedrich Feher) into the ravings of a madman; critics, beginning with Siegfried Kracauer, have argued that this change subverted Mayer and Janowits’ anti-authoritarian message, making it pro-authority. But this too-simple reading overlooks the way the film, with its jagged-edged sets, produces a generalized feeling of unease about reality that is more unsettling than any simple political allegory.

The film’s enduring power rests on three pillars: the intriguing script, the marvelous sets, and the performances of Krauss and Veidt. Feher, co-star Lil Dagover, and the other actors turned in performances that, while standard for silent films, now seem dated. But the two stage actors, experienced in expressionist drama, turned in highly stylized performances that fit almost perfectly with the world of the film. Veidt, with his stark white face, black leotards, whirlpool eyes, and balletic movements, is the center of our attention whenever he’s on screen. (As, for example, when a young man asks the fortune-telling Cesare, “How long will I live?” and Veidt, staring straight ahead, mouths, “Until tomorrow’s dawn.”) Kracauer has written that when Veidt’s Cesare “prowled along a wall, it was as if the wall exuded him.”

After the fame that Caligari brought Veidt, he did the occasional stageplay or one-night theatrical recital, but he mainly worked in films for the rest of his long career.

Master of Menace

In 1920 Veidt played a hypnotist, the composer Chopin, and the Devil again. Of particular interest is a lost film, The Janus Head, directed by Murnau for Lipow-film. This was a loose adaptation of Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, with the Jekyll/Hyde characters (played by Veidt) changed to Dr. Warren and Mr. O’Connor to avoid paying royalties to Stevenson’s estate. In the film it was a bust of two-headed Janus that periodically changed the virtuous Dr. Warren into the evil Mr. O’Connor. Warren’s butler was played by a relatively unknown stage actor, Bela Lugosi.

In 1922 Veidt played a maharaja in the epic The Indian Tomb. Veidt later remarked that while Caligari had won him a “highbrow” following, it was The Indian Tomb that brought him his first fan mail. To Veidt’s lasting grief, his mother died of a heart condition that January, only 56.

At a party that December he met Felizitas Radke, a poised young woman from an old aristocratic family. They were quickly taken with each other, they married in April 1923, and while it didn’t prove to be happily ever after, they were happy together for a long time.

In 1924 Veidt appeared as himself in an early documentary about filmmaking, and acted in two important films of the dark-fantastic, The Hands of Orlac and Waxworks. Orlac, produced in Austria and directed by Robert Wiene from a novel by Maurice Renard, revolves around musician Orlac (Veidt), who has the hands of a murderer surgically attached after his own hands are crushed in an accident. When a series of murders occur, Orlac comes to think that the hands are doing them with a life of their own. At the film’s Austrian premiere the audience was so disturbed by the film’s content that they began shouting angrily. Veidt walked on stage, talked about the making of the film, and calmed them down—a lesson to Veidt about the power of his voice and presence. (Happily, this film, long thought lost, has been painstakingly restored from three partial prints by LSVideo.)

Waxworks, Paul Leni’s directorial debut, was an anthology film in which a young writer imagines stories about three carnival wax figures, including Jack the Ripper (Werner Krauss) and Czar Ivan the Terrible, played with crazed intensity by Veidt.

His 1925 films included a Swedish-made and a French-made production. That August he was working on a German production set in Italy when he received word that Felizitas had given birth to their daughter. Vera Viola Veidt, who became known as Viola, would remain ever after the apple of her father’s eye.

Hollywood: The Joker’s Wild

In 1926 Veidt starred in Henrik Galeen’s remake of The Student of Prague. Veidt played the dual role of the student, Baldwin, who strikes a demonic bargain, and the evil doppelganger who results from that bargain. (Krauss played the demon bargainer, Scapinelli.) That fall, in response to an imploring cable from John Barrymore (“I won’t make the picture without you”), Veidt journeyed to the United States to appear with Barrymore in The Beloved Rogue. Barrymore’s first words when Veidt stepped off the train from New York were, “God, you’re really tall!”

The Veidts settled in Hollywood for a time, as film offers came in from several studios. Veidt signed a contract with Universal, run by German immigrant Carl Laemmle. Over the next couple of years Veidt made three films for Universal, notably playing Gwynplaine, whose face is mutilated into a permanent smile, in expatriate director Paul Leni’s The Man Who Laughs (1928). Batman creator Bob Kane later acknowledged that Veidt’s striking appearance as Gwynplaine inspired Kane to create The Joker.

The Veidts enjoyed relaxing and playing with their daughter in their Beverly Hills home, and enjoyed the company of the German immigrant community, including Murnau, Laemmle, and Greta Garbo, as well as the American-born Gary Cooper. But the coming of sound films inspired Veidt to return to Germany. He had been studying English steadily, but his grasp of it was still limited, his accent heavy, and he felt better equipped to make the transition to sound in his native land. The Veidts returned to Germany in 1929. One of the upcoming roles for which Universal had been considering Conrad was Count Dracula.

Back in Germany

Veidt felt that the poor mechanical quality of his first German sound film gave people the impression that his voice was at fault. But his next picture, The Last Company (1930) “was almost technically perfect.” German filmgoers discovered that this marvelous pantomimist had a subtle, versatile, musical voice.

In 1930 Veidt traveled to England for the German-language version of a film, and immediately fell in love with the country. The Other Side (1931), about the English army in WWI, was based on R.C. Sherriff’s play Journey’s End. (It was this British stageplay, and the American film of it, that forged the reputations of director James Whale and young actor Colin Clive.) In Rasputin, the Uncrowned Tzar (1932), Veidt portrayed the much-maligned Rasputin as a complex figure with both good and bad points. In the English language version of Floating Platform 1 Doesn’t Answer (1932), a science fiction story set on an airplane-refueling city in the mid-Atlantic, Veidt played a heroic pilot. In The Wandering Jew (1933) Veidt portrayed the sixteen century-old character of myth and legend.

To accomodate Veidt’s periapetic acting schedule, the Veidts moved several times during this late German period, including a temporary relocation to Vienna, Austria, while Conrad participated in a theatrical tour of the Continent. These frequent relocations, and the separations necessitated by Conrad’s acting schedule, gradually frayed his marriage to Felizitas, and in 1932 they agreed to a divorce. Felizitas kindly agreed to grant Conrad custody of Viola, but after further consideration Conrad decided that seven-year-old Viola needed the full-time parent that his work would not allow him to be. Conrad received generous visitation rights, and Viola would stay with him for certain parts of the year.

Veidt stoically believed that he would spend the rest of his life alone, save for the visits with his daughter. Then he began visiting a cabaret, The Two Lillies, one of whose co-proprietors was Ilona “Lilli” Prager, a Hungarian-born, Jewish divorcee. They grew close, and were married on March 30, 1933. For Veidt, the third time proved the charm.

Enemy of the State

Two months earlier, on January 30, Adolf Hitler had become Chancellor of Germany. Nazi Minister of Propaganda Goebbels was keen to have an actor of Veidt’s stature and abilities active in propaganda films—an offer that Wegener, Krauss, and others would accept. Veidt declined. The Nazi government mailed Veidt a questionairre. When he came to the space for identifying race and religion, Veidt, a Protestant, wrote “JUDE” (Jew) in large letters. Relations with the government began to cool. He applied for permission to move to Great Britain. After several red-tape delays Conrad and Lilli left Germany in late April.

The Veidts found a nice house in London, and Conrad quickly landed work with the Gaumont-British film studio, including I was a Spy (1933), in which he played a WWI German officer duped by a Belgian woman spy. This portrayal added to the Nazis’ growing irritation with Veidt. Late in 1933 Veidt was back in Berlin acting in William Tell, when the German government learned that Gaumont-British planned to star Veidt in the forthcoming film Jew Suss, based on a novel by Lion Feuchtwanger, in which a Jewish man named Suss is persecuted in 18th century Germany. The Nazis didn’t want the film made, and they definitely didn’t want Veidt to star. A note was sent to Gaumont claiming that Veidt was too ill to return to England. Meanwhile, Veidt was detained as a “guest of the state,” in a hotel room with a bed and a bath. He was not physically abused, but received regular verbal abuse from a Nazi officer, who demanded that Veidt decline the role in Jew Suss, and demanded that Veidt supply the names and addresses of his associates in Germany. Veidt refused both demands.

Veidt’s British producer, Michael Balcon, managed to get a British doctor to Veidt’s place of detainment, where the doctor certified him in good health and fit to travel. Then Gaumont-British and the British Consulate brought pressure to bear on the Nazi government, which eventually released him. Veidt returned to Lilli, having satisfied none of the Nazis’ demands. The Nazis banned him from returning to Germany, and he never did.

This England

During Veidt’s English period (1933-1940), while remaining active in films, he also indulged his wide range of interests. He enjoyed many sports, and listening to classical music. He read widely in fiction and nonfiction (including occultism; Veidt considered himself a powerful medium). He and his daughter usually had at least one dog or cat.

In a 1934 interview he spoke generously of his major romances: his first wife “was about as perfect as any wife could be. But I had not learnt how to be a perfect husband.” Veidt spoke of how he had searched all his adult life for a partner who could mother him, and found her in Lilli. (“She mothers her own mother.”)

Veidt attributed his success in acting to four things: driving ambition; will; luck—“And finally...there is a strange power which comes into me, magically it seems, and transmutes not only my inner but my physical being when I am called upon to express myself on the stage or before the camera....It is precisely as though I were possessed by some other spirit when I enter on a new task of acting, as though something within me presses a switch and my own consciousness merges into some other, greater, more vital being....In many actors the man and the actor are so indistinguishable that you can hardly tell where the man begins and the actor leaves off. Not so with me.”

Veidt smuggled his parents-in-law from Austria to neutral Switzerland. In 1935 he managed to get the Nazi government to let his ex-wife and daughter move to Switzerland. Viola stayed with her father for three or four months each year, until the outbreak of war. Veidt became a British citizen in 1939.

In 1935 Veidt played an angelic figure who touches the lives in a London boarding house in the allegorical fantasy The Passing of the Third Floor Back. He got to swashbuckle in Under the Red Robe (1937). In The Spy in Black (1938) he played a German submarine commander opposite Valerie Hobson’s British agent. Veidt’s performance here won the admiration of 16-year-old Christopher Lee, who soon after had the good fortune to meet and chat with Veidt on a golf course. In the French The Chessplayer (1938) Veidt played the 18th century maker of robots, Baron von Kempelen.

The Thief of Bagdad (1940), a big-budget fantasy, is one of Veidt’s signature films. It features a charismatic performance by Sabu, good special effects, and an entertaining story, but it remains especially fascinating for the chance to see Veidt’s grand villainy as the sorceror Jaffar.What menace he packs into his quiet, resonant voice, his German accent sounding appropriately exotic.

Contraband (1940), released shortly after the Blitz began and featuring scenes of the London blackout, starred Veidt as a Danish merchant captain and, for a welcome change, the romantic lead, again opposite Valerie Hobson as a British secret agent. The film includes a scene that is a good example of the understated power of Veidt’s acting. Veidt’s Danish ship is being stopped by a British naval vessel to search for possible contraband. One of Veidt’s crew compares this to encountering a German U-Boat, remarking that U-Boat commanders are very polite. Veidt says, very quietly, “Yeees.” Pause. “Afterwards.”

Hollywood: A Taste of Love and Glory

In April 1940 Veidt was asked to travel to America to deliver and help promote Contraband’s U.S. release (as Blackout), the film’s American profits intended primarily to benefit the British war effort. Veidt and his wife arrived in New York and, shortly after, he received a call from Louis B. Mayer of MGM inviting him to try out for the male lead (a German officer) in the WWII drama Escape. The Veidts took the train to Hollywood (Veidt disliked heights, and never flew). After shooting Escape Veidt planned to return to England to help the war effort, but MGM persuaded him that at 47 and with poor eyesight, he could better serve by remaining in the U.S. and making films with anti-Nazi content.

Veidt made substantial contributions of money and time to the British cause (as well as the American war effort, after Pearl Harbor). He was active in the European Film Fund, helping find work and housing for displaced European actors. He and Lilli provided a wartime home for the teenaged son of English friends. Veidt acted, without pay, in several WWII-related radio plays. In public addresses and interviews this great German actor became a symbol of resistance to Naziism.

For MGM Veidt played a cad taking advantage of a scarred Joan Crawford, the corrupt leader of a religious sect, and a Nazi agent. He was farmed out to Columbia to play a virtuous ballet master in love with Loretta Young in The Men in Her Life. For Warner Brothers he and Peter Lorre played Nazis.

In 1942 Warner’s requested Veidt as the Nazi villain, Major Strasser, in Casablanca. Veidt was enthusiastic about the unusually intelligent script-in-progress, and about the chance to work with Hungarian director Michael Curtiz, and with a spectacular cast including Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Claude Rains, Peter Lorre, Sidney Greenstreet, Dooley Wilson, and Veidt’s Austro-Hungarian friend, Paul Henreid. Veidt’s suave menace proved perfectly suited to the story. Casablanca racked up multiple Academy awards. It has grown, with time, into the quintessential American movie.

In Above Suspicion (MGM, 1943) Veidt played a witty Austrian freedom fighter. Veidt turned 50. He had made eight American films in three years. Film offers were coming in from MGM and other studios.

Until Tomorrow’s Dawn

Sometime in his 40s Veidt learned that he had inherited his mother’s weak heart, a condition aggravated by chain smoking. He took nitroglycerin tablets, and he and Lilli kept his condition secret so he could remain active in films.

The Veidts attended a late-night Hollywood party on April 2, 1943. Early the next morning Veidt accepted a golfing invitation. On the eighth hole Veidt suddenly gasped loudly and fell over. His doctor, playing on the same course, attended him until the ambulance arrived, but he was pronounced dead at the hospital.

Veidt, a consummate professional, took his work very seriously, but he didn’t take himself seriously. On-set he was free of prima dona behavior. Off-set, he was gracious and generous to fans.

Veidt’s performances in such films as Caligari, The Man Who Laughs, The Thief of Bagdad, Contraband, and Casablanca, apart from their excellence, have almost nothing in common. Veidt’s great versatility may be one reason why his name isn’t more familiar today. But interest in his career, long on the wane, is again growing. Of crucial importance, several of his films are now available for purchase and rental, including the five just mentioned (Film Preservation Associates has done an ambitious restoration of Caligari, including the original tints), as well as Eerie Tales, Waxworks, The Hands of Orlac, and The Student of Prague.

This suave, subtle actor mastered a wide range of roles; but his fans loved and love him best exploring our shared shadows. Apart from his performance in Casablanca, Veidt remains especially intriguing today for his mastery of the dark-fantastic. Before Karloff and Lugosi, before even Chaney, Veidt forged a reputation as a master of macabre roles, creating characters both frightening and sympathetic. Wegener and Krauss explored comparable roles beginning in the teens, but their stardom remained mostly confined to Germany. Veidt’s multi-faceted career extends well beyond the horror genre. But it needs to be said that, among his several achievments, he was cinema’s first true international horror star.

Sources: Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, 1947; Carlos Clarens, An Illustrated History of the Horror Film, 1968; Lotte H. Eisner, The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt, 1973; John D. Barlow, German Expressionist Film, 1982; R.V. Adkinson, ed., trans., Classic Film Scripts: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari by Robert Wiene, Carl Mayer and Hans Janowits, 1984; Jerry C. Allen, Conrad Veidt: From Caligari to Casablanca, 1993; David J. Skal, The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror, 1994; Dr. David Soren, The Rise and Fall of the Horror Film, 1995; Eric M. Heideman, “The Classic Horror Film: Of Germany and the Soul,” Darkling Plain #1, 2000; The Conrad Veidt Home Page; The Conrad Veidt Society Page; The German-Hollywood Connection; The Internet Movie Database; LSVideo.